Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

The tram through the park: the origins of the West Coburg tramway

I am one of the lucky ones. I’ve been riding the West Coburg tram through Melbourne’s Royal Park for over 60 years – starting as an infant on my mother’s knee. For me this line is the most picturesque on the network, primarily for its views of the parkland. Summer’s scorched grass and shady trees and winter’s soggy ovals and bitter winds have been my doorway between suburb and city. What scenery for the price of a tram ticket!

Through my years of tram travel, I've seen Royal Park’s landscape change. In my school days it seemed an endless carpet of golf fairways, football ovals and cricket fields where I played sport. In the 1980s the park underwent a significant change and much of its area was replanted with native bushland. In recent years the Children’s Hospital has expanded and the netball and hockey stadia have grown larger. But the views of the parkland still remain a highlight for me.

The park’s origins date from the 1850s. A reservation of four square miles (10 sq km) was set aside for public recreation, as was common in many nineteenth century cities. In the early years it became the home of the Zoo and many public welfare institutions and it was the departure point for the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition in 1860.

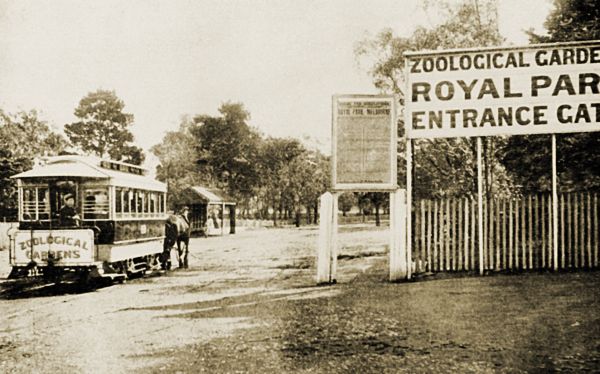

The Zoological Gardens were a major attraction within Royal Park from the 1860s. Between 1890 and 1923, this horse tram carried passengers from the Brunswick cable tram stop at Royal Parade and Gatehouse Street to the Zoo’s southern entrance. It was the first tramway through the park.- Photograph from the Mal Rowe collection.

In the 1880s, the park was bisected by the Melbourne to Fawkner railway and during WWII, the southern section was the site of a US military base, Camp Pell. After the war, these deteriorating buildings became the much criticised transit camp for homeless families, dubbed Camp Hell. It was dismantled just prior to the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games.

The unique geography of the tramway with its twists and turns through the park and the suburbs to its north has led me to wonder at its origins. In particular, why does the tramway cross such a large expanse of parkland instead of following one of the roadways along its boundaries? Surely Royal Park Station already provided transport for patrons of the Zoo and the sports fields.

I set out in search of some answers. What I found has given me new insight into the politics of transport development and the history of my local suburb.

Before the houses came

Today as I stand at the corner of Melville Road and Bell Street waiting to ride the number 55 tram to the city, I can still remember what this spot was like back in the late 1950s. Most of the houses and shops are the same, but many now stand vacant and forlorn while motor traffic regularly clogs the intersection and surrounding streets.

However, if I had stood at this spot decades earlier in 1916, the panorama would have been completely different. This was farmland with few buildings in sight. Plans for residential subdivisions had been drafted, but development was slow.

A mile (1.6 km) to the east were the Fawkner to Melbourne railway, the new North Coburg to City electric tram in Sydney Road and a growing commercial and residential area.

To the south through West Coburg and West Brunswick, it was mainly paddocks with some housing clustered in West Brunswick. Travel through these areas was along disconnected tracks, unsealed and full of pot holes.

Further south lay the large expanse of Royal Park. Although numerous sections had been excised from the original reservation, the trustees remained tenacious in their defence of the park’s primary purpose. North-south roadways were not permitted through the park. In hindsight, perhaps we should be grateful for their tenacity.

Aerial view of Royal Park looking south east towards Melbourne (c1940). Note the government institutions in the foreground, the zoo in the mid ground and the railway and tramway tracks.- Photograph courtesy State Library Victoria.

With such travel impediments, landowners and residents in the west were forced to use the increasingly congested Sydney Road/Royal Parade corridor. Land values close to Sydney Road rose as industry and its workforce clustered close by. But land to the west remained semi-rural and its value languished – a cause of much discontent. It seemed to some that Sydney Road had all the luck.

Dominance of Sydney Road

Sydney Road has always been busy in my memory – an endless line of shops and cars crossed by dozens of narrow streets. Housing from the late 1800s can still be found close to Sydney Road along with remnants of factories and warehouses from the same era. They make for some interesting local history walks.

A Brunswick cable tram in Royal Parade (c1930) providing a frequent service between the city and Sydney Road. Note the longer trailer for the higher passenger numbers on this busy route.- Photograph courtesy State Library Victoria.

Sydney Road’s dominance was preordained in the first years of white settlement, when chief government surveyor Robert Hoddle mapped the area in 1837-38. He laid out elongated east-west farming lots either side of one main north-south thoroughfare, which became Sydney Road.

Farm traffic on this muddy track was soon joined by traffic to Pentridge Stockade and Prison. Hotels and shops were built to supply the needs of locals and travellers. Quarrying, brickmaking and other industries brought employment, housing and further traffic. By the 1880s this activity attracted the railway and the cable tram with connecting horse tram.

The Sydney Road corridor was a magnet for industry and newly arrived migrants seeking jobs; the western parts of Brunswick and Coburg could not compete.

Brunswick’s population figures of that time illustrate the settlement patterns. While Brunswick’s total population rose from approximately 14,000 in the 1880s, to 24,000 in 1901 and 44,000 in 1921, only 12%-15% of these residents lived in West Brunswick (2,800 in 1901; 7,000 in 1921). It was a similar story in the more lightly populated Coburg.

Attempts to develop the west

Landowners in the western parts of Brunswick and Coburg viewed Royal Park and Sydney Road’s dominance as the cause of their low financial returns. Like landowners today, many were keen for development – and this required accessible transport.

Proposals for a “Moonee Vale Railway” [sic] running through West Brunswick and West Coburg were mounted in 1890, 1900 and 1909, but each proposal was defeated. In 1892 the Argus condemned it as a scheme to use government funds to raise the value of land owned by speculators, some of whom were members of parliaments themselves. Nothing was ever built but part of the reservation can still be seen on modern street maps to the east of the Tullamarine Tollway.

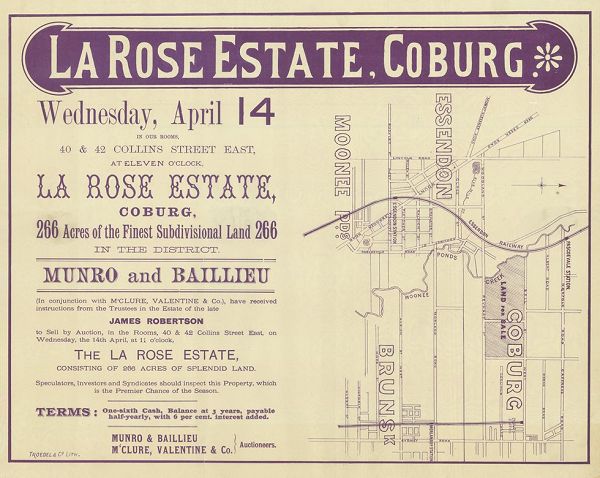

Poster advertising an auction for the La Rose Estate, Coburg (1886), one of several developments that would have profited from the proposed railway. Note that the agents Munro and Baillieu were prominent landowners who subsequently became a Victorian Premier and an upper house MP respectively.- From the Troedel collection, State Library Victoria.

In the early 1900s many local progress associations and advancement leagues were established. Newspapers of the day carried reports of ratepayers’ meetings at which motions were drafted complaining of their isolation and lack of advancement. Tramway routes were proposed and deputations made to municipal councils.

One humorous newspaper report from July 1914 recounts a lively meeting of 300 people conducted by the West Brunswick Direct Communication League at the Brunswick Town Hall. Speakers argued that Brunswick was being planned like a cheese board with no connected streets, and that West Brunswick was blessed by nature but cursed by the apathy of indifferent councillors.

One speaker announced that residents did not want a railway anymore but something more modern – perhaps even an aeroplane. With an eye to the future, Mr Jewell MLA suggested a tunnel under Royal Park for road or tramway connection with Melbourne. The tunnel did not eventuate and it still appears to be an unacceptable solution to traffic congestion today.

With increasing public agitation, local councils moved into the transport business. The Melbourne, Brunswick and Coburg Tramways Trust (MBCTT) was established by these municipalities to build electric tramways from Coburg to the city.

In 1915, as its North and East Coburg routes were under construction, the trust commissioned a report on the feasibility of a West Coburg tramway. The engineer’s report recommended a route from Gaffney and Sussex Streets, along various streets in West Coburg and West Brunswick, through Royal Park and into Queen St, Melbourne.

But to the western ratepayers’ dismay, the Trust rejected this proposal. While the Trust’s North and East Coburg lines proved to be well engineered, well administered and profitable, the Trust was not prepared to build a tramway in the west. Facing land access difficulties and low fare revenue from a small population, it is likely the Trust applied its financially responsible criteria to the West Coburg proposal and found that it did not stack up.

By 1916, locals would have wondered if a transport link from West Coburg to the city would ever eventuate. But what seemed impossible then was to become a reality by 1927.

Fortune smiles on the west

So what changed the fortunes of West Coburg and West Brunswick? It was a mix of several favourable factors. Alone each lacked enough impetus; together they became a compelling force, difficult to resist.

| 1. | The government decided that a growing Melbourne needed a more comprehensive street transport system and that a tramway monopoly was the way to achieve it. This had been a recommendation of the 1910-11 Royal Commission, along with the electrification of the suburban railways and the removal of all level crossings – a work still not completed today. |

| In 1918, the government side-stepped a turf war with the municipalities about tramway ownership and established its own government authority, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board (M&MTB). This Board was charged with developing a metropolitan wide network and it was given the authority to do its job. | |

| 2. | The government also wanted to stimulate the Victorian economy. Building an integrated tramway system would go some way to satisfying this goal. The state’s economy had not performed well since the 1890s depression and Victorians had an expectation that the government would enable improvement. The government was unpopular and parliament volatile, with industrial unrest giving voice to this dissatisfaction. |

| 3. | Once established, the M&MTB was eager to develop its tramway network. Under the dynamic leadership of Chairman Alex Cameron, it researched population figures and transport flows that showed that West Brunswick and West Coburg were the most deserving of a new “green fields” tramway. From this research it produced a master plan, known as the General Scheme. Cameron – formerly chairman of the Prahran and Malvern Tramways Trust – had been instrumental in building new tramways leading to commercial and residential development in the southeastern suburbs of Melbourne. He was confident that a new tramway would do the same in West Brunswick and West Coburg – and in many other suburbs – if the General Scheme was even partially implemented. |

| 4. | The Royal Park Trustees, long time opponents of transport corridors through the park, were facing significant public criticism in the 1920s. When the M&MTB came to negotiate the tramway, the trustees’ resolve had weakened. The park was described as little more than a large open paddock where stock grazed for a fee and sporting clubs hired the limited facilities. Lack of funds had restricted park maintenance and development since its inception. |

| The M&MTB won agreement from the trustees to build a tramway, adjusting the route around a number of recreation facilities to satisfy the trustees’ concerns. | |

| 5. | The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Railways was potentially a more difficult opponent. However, the political realities of 1922-23 appear to have weakened this body’s resolve as well. |

| The Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Act (1918) required that expenditure exceeding 10,000 pounds (increased to 20,000 pounds in 1920) was to be submitted to the standing committee for approval. It was thought that this would be a brake on extravagant projects as a majority of committee members came from rural constituencies, naturally being reluctant to fund a new suburban tramway. | |

| True to expectations, in 1922 the committee tried to cut back the M&MTB’s proposed route. Initially it recommended only the section between Moreland Road and Royal Park Station, arguing for the protection of railway revenue. Faced with the Board’s research data, loud public support for the tramway and the government’s need for improved popularity, the committee twice revised its recommendations. | |

| Just months later it conceded that the tramway from Moreland Road to Royal Park Station could continue to the city. It would travel through the middle of the park, along Flemington Road, Peel Street and William Street to Collins Street. Strategically the Board had also proposed that the Essendon and Maribyrnong River tramways could be extended into the city using the same route, adding to the attractiveness of the proposal. | |

| Then in early 1923 the committee reconsidered again and recommended that the tramway be extended to Bell Street and eventually further north. |

At last the way was clear to build the long sought after direct transport connection between West Coburg and the city. Such a change of fortune in just a few years!

1925

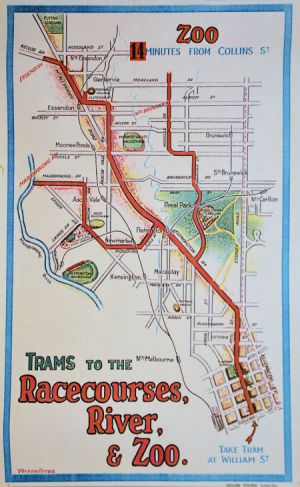

M&MTB publicity poster promoting three new electric tram services

from William Street to recreational venues. (Click on image to see

a larger version.)

1925

M&MTB publicity poster promoting three new electric tram services

from William Street to recreational venues. (Click on image to see

a larger version.)- Image courtesy State Library Victoria / Vernon Jones.

The M&MTB’s route

Several alternate routes had been proposed by various bodies over the previous decade, each with its own rationale. The M&MTB’s route was designed to maximise the line’s future passenger numbers. What appears to have underpinned its proposal was the West Coburg line’s place in the “big picture”. This line was to be the first of many new lines – an early piece in the jigsaw that was to soon become an extensive metropolitan tramway network.

Tram 221, the third W class built, waits for passengers at the Zoo platform stop just south of the Melbourne to Fawkner railway embankment (c1925). Its destination was likely the temporary terminus at Daly Street or Albion Street, West Brunswick. Note the absence of a route number box on its roof and the picket fence around the Zoo.- Photograph from the Ron Scholten collection.

The following considerations were key in the choice of the M&MTB route :

- William Street was preferred to the earlier MBCTT proposal to use Queen Street. Both would avoid the cable tram in Elizabeth Street, but William Street would better serve the city’s western end and would also better suit a future southern extension over the Yarra River.

- The wide boulevards of Flemington Road and Peel Street were preferable to the Howard Street and Courtney Street route proposed by the MBCTT. Flemington Road would provide a direct city route from three tram destinations: West Coburg, Essendon and Maribyrnong River. Early discussions considered three tracks, one being for express services. Flemington Road would also provide a connection with the Elizabeth Street and Abbotsford Street cable trams.

- While the Royal Park Trustees and others proposed routes along the park’s eastern or western boundaries, the M&MTB’s preferred route through the middle of Royal Park would have several advantages: redirect some passenger traffic away from the congested Sydney Road corridor; maximise the tramway’s appeal to passengers as the quickest route between the city and West Coburg; and, service Royal Park Station and the Zoo’s northern entrance.

- In West Brunswick and West Coburg, the M&MTB preferred a route that was a mile (1.6km) west of the Fawkner railway because it would maximise the new tramway’s future catchment area. Research had shown that passengers were prepared to walk up to half a mile (0.8km) but little more. This differed from the MBCTT proposal that suggested Grantham Street and Pearson Street. As no suitably located north-south roadway existed a mile from the railway, the M&MTB proposed to build one. It would extend the existing half mile (0.8km) Melville Street in West Brunswick into a two mile (3.2km) north-south roadway for the tramway and motor vehicles.

- North of Bell Street, the M&MTB preferred a Derby Street route rather than a Sussex Street route as proposed by the MBCTT. Again this was because it would maximise the passenger catchment area. Although this extension was never built, this preference probably influenced where the new Melville Road would be built through West Coburg.

Construction began in early 1923 and was completed by June 1927. Tram services began in stages: from the city to Daly Street in July 1925, to Albion Street in October 1925, to Moreland Road in May 1927 and finally to Bell Street in June 1927. The winding route that the tram takes through the park and suburbs tells the story of its construction.

Since 1927 the tramway between Bell Street and Collins Street, City has remained relatively unchanged. The addition of a new city terminus at the corner of William Street and Dudley Street in 1944 and the duplication of the track between Reynard Street and Bell Street in 1946 were the only major changes.

Tram 344 using temporary track in Melville Road, West Brunswick (1968). The track in this narrow section of Melville Road was first laid as single track in 1925 and duplicated in 1927. In 1968 it was re-laid in mass concrete using work practices that differ markedly from those of 2016.- Photograph courtesy Mal Rowe.

Fortunes change

Fortunes changed for the M&MTB and the West Coburg tramline in the mid 1920s. The fortunate mix of factors that had enabled the line to be built to Bell Street did not last long. General economic conditions and the cost of building new electric tramcars and replacing the cable tram system were making it more difficult for the M&MTB to finance new routes. Numerous calls were made for the line to be extended north of Bell Street as recommended, but to no avail.

Other tram route proposals were similarly affected. With the coming of the 1930s depression and WWII any lingering hopes for further network expansion evaporated.

However, investment did return to the West Coburg line - but in a southerly direction rather than the proposed extension north of Bell Street. During WWII most tram routes were working to capacity, including the West Coburg line which ran though the US military base in Royal Park, named Camp Pell. The St Kilda Road/Swanston Street corridor had become severely congested and a new tram route into the city for southern tramlines was desperately required. Queens Bridge and William Street were the answer - as foreseen in the 1920s General Scheme.

In 1944 an electric tramway was built connecting William Street to existing track in the southern part of Hanna Street (now Kings Way), South Melbourne. A new terminus was installed near the Victoria Market at the corner of William and Dudley Streets.

Tram 599 preparing to depart the William Street terminus for St Kilda Beach (1966).- Photograph courtesy Mal Rowe.

When these new southern services to Dudley Street began in early 1946, West Coburg trams were extended to St Kilda Beach and some southern services were through-routed to West Coburg.

As a school boy in the 1960s, I frequently rode these trams. It was a novelty to see the variety of destinations displayed as they departed West Coburg for Carnegie or other distant suburbs. I can also recall the conductors from southern depots struggling with the unfamiliar street names and correct fares.

The West Coburg to Domain Road (now Domain Interchange) tramline has remained much the same ever since. A summary of the key stages of its planning and construction is contained in the attached timeline.

Shaped by the tramway

The West Coburg tramway had a profound effect on the suburban development of West Brunswick and West Coburg before the widespread adoption of the automobile. Residents in their thousands bought homes close to the new line with Californian Bungalows and other inter-war homes filling the surrounding streets.

In the 1950s when my parents built our weatherboard home on one of the few remaining vacant blocks close to the tramline, they were completing the residential development fed by the tramway 30 years earlier. Today these same homes are being bought and renovated by a younger generation, happy to be within walking distance of the same tramway.

When I began my research for this article, I imagined the long ride through Royal Park as an unprofitable route for a street tramway. But I now see it was the key to shortening the travel time of passengers from West Brunswick and West Coburg, whose patronage ensured the tramway’s success. For decades Royal Park had been a barrier to city access; after the tramway was built it became a doorway between suburb and city – one that many have enjoyed over its 90 years.

Travel on the West Coburg tram line also provides a tour of the inter-war and post-war suburban architecture of Melbourne. The character of these suburbs was shaped by the old W class tramcars that carried countless workers, housewives and children (including this writer) through its streets for decades. Growing up here nurtured my life long interest in Melbourne’s trams.

If you have not ridden the West Coburg tram in recent years or at all, why not take a ride? Pack your camera and Myki card, and catch the number 55 tram to sample the delights of the tram through the park and the suburbs beyond.

Bibliography

Burchell, Laurie (1997) The Railway Line that Never Was, Coburg Historical Society Newsletter, No. 49 June 1997

Brunswick & Coburg Leader (1914) Mass Meeting in Town Hall, 24 July 1914, page 1

Dunn, Peter (2000) Camp Pell, ozatwar.com, 7 August 2000

Jones. Russell (2003) Hooves and iron: Melbourne’s horse trams, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Jones. Russell (2003) Victoria’s tramway heritage, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Jones, Russell (2004) Fares please! An economic history of the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Jones, Russell (2007) Penny fare to Pentridge: the Melbourne, Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Jones, Russell (2008) Steady as she goes: the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Jones, Russell (2009) Alex Cameron: father of Melbourne’s electric trams, Friends of Hawthorn Tram Depot

Lovell, Peter (2014) East West Link (Eastern Section) Comprehensive Impact Assessment, Lovell Chen Melbourne, February 2014 pp 47-97

Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works maps (1896 - 1935, scale 40:1 and 160:1, online and hard copy), State Library Victoria

Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (1910-1922) graphs & data [cartographic material] : relating to population & its distribution, tramway & railway traffic for the metropolis, State Library Victoria

Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (1923) Proposals for general scheme, State Library Victoria

Melbourne to West Brunswick Construction Act (1922)

Prentice, R.H. (1966) A Brief History of the Melbourne, Brunswick and Coburg Tramways Trust, Running Journal, Tramway Museum Society of Victoria, July 1966

Richardson, J A. (1963) The Essendon Tramways (Second Edition), Traction Publications. 1963

Shand, Adam (2014) Camp Hell, adamsh.wordpress.com, 25 July 2014

South Melbourne to Melbourne Tramway Construction Act (1943)

Summerton, Michele (2010) Thematic History (Revised), completed for City of Moreland, Historica, May 2010

The Argus (1892) The Pascoevale Railway Scheme, 19 July 1892, p 5

The Argus (1911) West Coburg Extension, 16 December 1911, p 22

The Argus (1919) West Brunswick Tramway, 21 March 1919, p 7

The Argus (1923) New Electric Tramway For City, 21 April 1923, p 19

The Argus (1923) Solid Foundations For New Tramway, 26 July 1923, p 7

The Argus (1923) Flemington Rd: Three Track Reconstruction, 11 December 1923, p 15

The Argus (1925) New Electric Trams, 15 July 1925

The Argus (1925) New Electric Tramway Opened, 20 July 1925, p 9

The Argus (1925) William St Trams: Successful Inauguration, 20 July 1925, p 15

The Argus (1925) Electric Tram Extension, 21 August 1925, p 12

The Argus (1944) No Extension Of West Coburg Tram, 21 September 1944, p 3

The Coburg Leader (1912) West Brunswick Tramway League, 27 September 1912, p 1

The Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Act (1918)

An Act to amend The Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Act 1918 (1920)

Victorian Government Gazette (1925) Approval to Construct Electric Tramway from Moreland Rd to Bell St, West Coburg, 25 February 1925, p 678

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the following for their assistance:

Laurie Burchell and other members of the Coburg Historical Society

Adam Chandler, Melbourne Tram Museum

Noelle Jones, Melbourne Tram Museum

Russell Jones, Melbourne Tram Museum

Mal Rowe, Trams Down Under

Ron Scholten