Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Tramway ANZAC: Henry Thomas Anthony

Boer War veteran

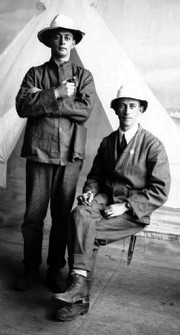

Henry ‘Harry’ Anthony (seated, on right) was 43, married with three sons, and working for the Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company as a gripman [1] at Clifton Hill Depot when he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 30 June 1915.

He was born in the inner suburb of Carlton in 1872 to Albert and Lucy (nee Moore) Anthony. In 1900 he married Jessie Hart Meldrum, listing his occupation as lorry driver. Shortly after the marriage, Anthony volunteered for service in the Boer War. He was assigned to the 5th Contingent, Victorian Mounted Rifles (VMR), which sailed for South Africa on 15 February 1901.

The origins of the Boer War of 1899-1902 were complex. The independent Dutch-speaking Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State in Southern Africa were suspicious of British imperial ambition. Two decades previously there had been war between the Boer republics and the British forces in the Cape Colony, which resulted in a Boer victory.

Since that time, many British subjects had entered the two republics in search of gold and diamonds. In order to forestall any British coup, in 1899 the Boers launched a pre-emptive attack on the Cape Colony. In response, the British Empire flooded over a hundred thousand soldiers into South Africa, determined to uphold imperial prestige, retain British territory and crush the Boer republics. Among those troops were volunteer units from the Australian colonies.

The volunteers had signed up for a twelve month period, and had to pass riding, shooting and physical tests.

By the time the 5th VMR arrived in the Cape, the conflict had regressed to a guerrilla campaign. The Boer irregulars specialised in hit and run tactics, against which the British had no effective doctrine. Neither the British Army nor the colonial volunteers were trained for this type of war.

The troops of the 5th VMR were largely engaged in interning women and children into concentration camps, together with burning crops, confiscating livestock and destroying homesteads. The objective was to starve the Boers into submission. The 5th VMR also formed mobile bands roaming hostile territory, intended to draw the enemy into combat where they could be defeated by the superior numbers of the Imperial forces.

On 12 June 1901, the left wing of the 5th VMR – including Anthony – was detached from a column in the eastern Transvaal by General Beatson, a cavalry officer serving in the British Indian army. It was placed under the command of an inexperienced Royal Field Artillery officer, Major Morris.

They camped at a farm called Wilmansrust, where Major Morris set picquets, or outlying guard posts, and ordered rifles to be stacked according to King’s Regulations away from the bell tents where the troops slept.

Boer guerrillas attacked that evening under the cover of darkness. They killed the regimental surgeon and 18 other ranks, and wounded five officers and 36 other ranks. The unarmed troopers could not reach their weapons, and were unable to return fire. Those troopers who did not abandon the position were captured, while the guerrillas looted the camp of arms, ammunition and other supplies. Once the Boers stripped the camp, they released their captives, and faded back into the night.

General Beatson accused the Victorians of being ‘white-livered curs’, and a ‘useless crowd of wasters’. At the subsequent court of enquiry, the senior Victorian officer was relieved of command, despite him not being in command of the operation. Major Morris was given a mild censure for posting inadequate picquets.

The following month, after being ordered out on a patrol a Victorian trooper was overheard by British officers saying that ‘…It will be better for the men to be shot than to go out with a man who called them white-livered curs…’. He and two other troopers present during the incident were arrested, court-martialled and summarily sentenced to death.

When this action caused unrest amongst the colonial troops, Lord Kitchener – the British High Commander – intervened and commuted the sentence of the troopers. It took the intervention of the Australian Prime Minister and an appeal to the King to have the Victorians released from an English jail and returned to Australia.

Due to this incident, as well as the better-known case of ‘Breaker’ Morant, the new Australian Government determined that members of the Australian armed forces would not be subject to capital punishment. This would be an ongoing source of friction between the British High Command and Australian commanders during the First World War.

Anthony left South Africa with the 5th VMR after the Boer War ended in February 1902. For his military service Anthony was awarded the Queen’s Service Medal with three clasps: Cape Colony, Orange Free State and Transvaal.

While Anthony was away on active service, in early 1901 his wife bore his first son, Leslie Archibald. More sons followed on his return – Henry Thomas in 1906 and Albert Stanley in 1908, when the family was living in Hotham West (now known as North Melbourne). Tragically, their fourth son Norman died in 1911, only 23 days after his birth.

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, enlistment in the AIF was restricted to men between 18 and 35, although in practice these limits were frequently breached. When Anthony enlisted in June 1915 at the age of 43, he was significantly older than the upper limit. No doubt his previous military experience in the Boer War was a key factor in the acceptance of his enlistment, and also for his allocation to the 9th reinforcements draft for the 4th Light Horse Regiment as a Trooper. However, his age and general level of health and fitness would be the defining factor in his service in the First World War.

After initial training, the reinforcements draft left Melbourne on board HMAT Hororata A20 on 27 September 1915, bound for the Middle East. On arrival in Egypt, the troops proceeded to training camps.

By the time Anthony’s training was complete, the Gallipoli campaign was in its final stages before evacuation, so the reinforcements were not embarked for Anzac Cove. The return of the Anzacs from the Dardanelles in late December 1915 saw the battle-weary troops rested, a rest they sorely needed.

In March 1916, the Australian infantry battalions were formed into the First and Second Australian Divisions, in preparation for redeployment to France and the Western Front, while the Light Horse regiments were to remain in Middle East, to defend the Suez Canal against the Ottoman Empire. Anthony was not to stay with the 4th Light Horse – on 21 March he was transferred to the Cyclist Corps, for redeployment with the First and Second Divisions. He sailed for Marseilles on the SS Briton on 25 March, arriving five days later.

He was taken on strength of the 1st Anzac Cyclist Battalion on 12 May 1916, in Étaples in the Pas-de-Calais, Northern France.

The cyclists were primarily used as despatch riders. During major offensives they were used in a similar manner to cavalry. They were less flexible and mobile than cavalry, but they were much less expensive to maintain. When not acting in their primary role, the cyclists were assigned other duties such as directing traffic, unloading railway wagons, or acting as burial parties.

However, it appears that Anthony’s age was becoming an issue. He was admitted to hospital on 24 June with acute lower back pain. After a short convalescence, Anthony was posted to the AIF surplus pool. It was not until 9 September 1916 that he received a posting to the 13th Light Horse, the only Australian Light Horse regiment in France. This regiment was the cavalry unit for I Anzac Corps.

He did not last long with the Light Horse. On 4 November Anthony was transferred to the Military Police, but he fell seriously ill, and was admitted to hospital on 1 January 1917 with bronchitis and pleurisy. After a lengthy convalescence in England, he was assigned to AIF Headquarters in London on 13 June.

Anthony remained in London until his health declined further. He was examined by a medical board on 20 February 1918, when he was found to be suffering from arteriosclerosis and emphysema. He was detached from duty on 16 March 1918 and sent to 2 Australian Command Depot at Weymouth to convalesce. While there, he was scheduled for discharge as unfit, and sent back to Australia on HMAT Marathon A74, which left Plymouth on 15 April 1918.

He was discharged in Melbourne, on 22 May 1918. When Anthony was reunited with his family, he met for the first time his fifth son, Lindsay Lorraine – born in early 1916, while Anthony was away on active service.

Anthony was issued with three service medals: the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal, and the Victory Medal.

The returned ex-serviceman was awarded a disability pension of £2/8/9 per fortnight from 25 July, and he re-joined the tramways. He became active in the tramways union, the Australian Tramways Employees Association (AETA), becoming a workplace delegate at North Carlton Depot. Anthony was elected to the AETA 8-Hour Committee in 1924. It would be interesting to speculate how much his military service influenced his involvement in union affairs.

Post-war, Anthony worked in North Carlton and Brunswick cable tram depots, and then at the Coburg electric tram depot. However, his health was declining, so he retired from the tramways service. In 1929, he was admitted to the Caulfield Military Hospital, where he died on 6 October, aged 57, survived by his wife Jessie and four sons.

His funeral was held on 8 October. The cortege left his residence at 6 Dunstan Street, East Brunswick, at 11 o’clock for Fawkner Cemetery. A special tram – organised by his former comrades from the union – was put on to carry mourners from Albion Street to the Baker Street terminus in North Coburg.

Anthony was buried in the Church of England section of Fawkner Cemetery.

Bibliography

The Age (1924), Industrial News, 19 December 1924

The Argus (1924), Work & Wages, 19 December 1924

The Argus (1929), Deaths, 8 October 1929

The Argus (1929), Funeral Notices, 8 October 1929

Australian War Memorial (1915), First World War Embarkation Rolls

Australian War Memorial (2015), Australia and the Boer War, 1899-1902

P.L. Murray (1911), Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa, Department of Defence

National Archives of Australia (1914-19), Henry Thomas Anthony – Service Record, Commonwealth of Australia

The Railway and Tramway Record (1924), Victorian Branch No. 1, January 1924

The Tramway Record (1929), Obituary, 31 October 1929

Graham J. Whitehead (1998-2006), Wilmansrust: The Debacle In South Africa, Kingston Historical Website

Footnote

[1] Gripman was the standard term used in Melbourne for a cable tram driver.