Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Travels in the dark: all-night trams in Melbourne

As all Australians know, there has been a long-standing rivalry between Melbourne and Sydney, ever since the days of the gold rush in the 1850s when Melbourne became the wealthiest city in the world. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Sydney had overtaken Melbourne in many aspects, including population, as the southern city was still suffering the after-effects of the 1890s economic crash.

One of the areas in which Sydney had stolen a march over Melbourne was the provision of all-night public transport. While the late evening streets of Melbourne were serviced only by horse-drawn hansom cabs, Sydney had introduced hourly all-night electric tram services from 1901, initially on the Leichhardt and Dulwich Hill lines, but later extending to the remainder of the network.

Unlike Sydney, with a tramway system run by the government-owned state railways, in 1901 Melbourne's cable trams were operated by a private company, the Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company (MTOC). Under the management of its formidable chief executive, Francis Boardman Clapp, the Company was focused on returning solid dividends to its shareholders. Lightly patronised night services would be unprofitable, so demands for all-night service were dismissed by MTOC.

A financial loss for all-night services was inevitable due to MTOC’s high fixed operating costs, as each of the steam-operated engine houses driving the cables required a full engineering crew, no matter how many or few cable trams were run. Consumption of coal by the engine houses – another major operational cost – was also relatively unaffected by the density of tram traffic. Therefore, MTOC had little incentive to run all-night services, as the Victorian State Government of the time was extremely reluctant to offer a subsidy for all-night services, to what was a very profitable private company.

When the public lobbied MTOC in 1911 requesting all-night services, the company strongly rebuffed the demand due to economic reasons. The suggestion that it substitute horse-drawn trams at night to reduce costs was rejected with the assertion that it would be a backward step. The company also stated it was reluctant to enter into a major investment enabling all-night services, as it had only a little more than five years for its operating lease to run, limiting the time to recover any related costs. For this reason, MTOC also ruled out modifying any of its tramcars with direct-drive petrol motors or petrol-electric propulsion.

That was where the matter of all-night trams rested, at least until the formation of the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (M&MTB) at the end of the decade.

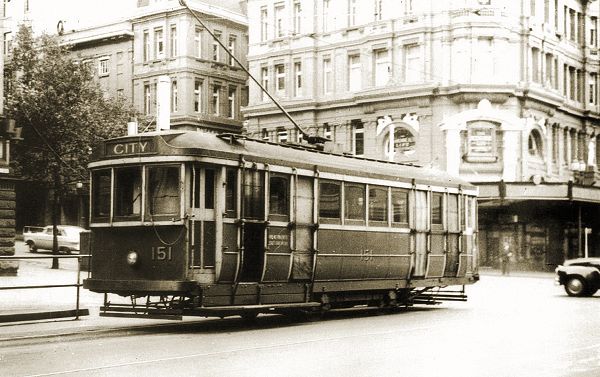

1950s view of M&MTB R class 151 in Swanston Street. The tram shows the result of nearly two decades of hard service as an all-night car.- Photograph from the Ron Scholten collection.

In 1920, the Board considered a trial all-night tram service. However, like MTOC it ruled out introducing all-night cable trams, for exactly the same reason: high fixed operating costs. Much of the M&MTB’s electric tram network was likewise considered unsuitable for all-night service, as a key element of successful operation was access to the central business district. The cable trams had a virtual lock on accessing the city, blocking the former municipal electric tramways.

However, the former Hawthorn Tramways Trust electric line terminated at Princes Bridge, at the edge of the city. The M&MTB therefore resolved to hold a six-month trial, running an hourly service between 1am and 6am, from Princes Bridge along Batman Avenue, Swan Street and Riversdale Road, to terminate at Camberwell Junction.

The trial commenced on 14 March 1921, using trams with two-man crews. Fares were set at a higher level than those for normal day services – 3d for one section, 6d for two sections, 8d for three sections, and 2d for each additional section. No concessional fares were available for children, so they had to pay the full adult fare to travel on an all-night tram. For comparison, normal adult fares were 1½d for one section, and 1d for each subsequent section. On completion of the trial at the end of September 1921, the M&MTB decided not to implement a permanent all-night service due to the financial loss incurred. Lobbying from the Australian Railways Union, whose members found the all-night service valuable for going to and from their jobs, did not persuade the Board to reverse its decision.

Periodically, implementation of all-night trams was reconsidered, but no further action was taken until after Alex Cameron was replaced as M&MTB Chairman in 1935 by H.H. Bell. On 3 September 1936, the Board decided to implement an all-night electric tram service in conjunction with introducing a Sunday morning service [1] on both cable and electric lines.

There was considerable opposition to the implementation of all-night trams. For some time, private bus lines had been providing a profitable all-night service across the city, so naturally the Motor Omnibus Proprietors Association and the Commercial Motor Users Association lobbied the Minister for Public Works [2] against the M&MTB proposal, as they believed it was unfair for a government statutory authority to be competing against private interests. The bus proprietors came under attack for their position, as a case of vested interests protecting their privileges to the detriment of public benefit, although they did have support from one Melbourne City Council councillor, J. Hardy. Unfortunately for the bus proprietors, Cr. Hardy did not receive support from the other councillors.

Some members of the public also objected, both on their own behalf and on behalf of hospital patients, on the basis that the noise of electric tramcars in the early morning would interrupt their rest. Others objected due to taxpayers funding the expense of all-night services, as the M&MTB was a government authority, or they supported the rights of the bus line proprietors.

The most trenchant opposition against the introduction of all-night trams was from the Baptist Union, which held that they would “destroy the very fabric of our social and moral life” by “encouraging young people to attend parties and dances that ran into the early hours of the morning”.

Despite the opposition, the M&MTB pressed on with the implementation of its new all-night tram service, stating that it paid substantial costs for maintaining the roadway between its tracks, together with municipal rates for the land it used, and should be entitled to maximise its return on investment by running an all-night service to cover these costs. Bell said that “Melbourne had for far too long lagged behind the other large cities of the world in the provision of that facility for rational enjoyment and convenience”. The first all-night electric trams started running on the evening of 14/15 February 1937, on three routes:

- Coburg to St Kilda Beach

- North Coburg to Camberwell, via Sydney Road, Victoria Street, Swanston Street, St Kilda Road, Malvern Road and Burke Road

- Essendon to South Caulfield Junction via Flemington Road, Victoria and Swanston Streets, St Kilda Road, Fitzroy Street, Carlisle Street, Brighton Road and Glenhuntly Roads.

Ten one-man cars were used for the initial service. Other routes would have to wait until more single-truck tramcars were modified at Preston Workshops for all-night service. Fares were set at 4d for one or two sections, and 8d for a through journey from one of the suburban termini to the city. If a passenger wished to travel beyond the city while remaining on the same tram, a second fare was due. As in the trial sixteen years previously, no concession fares were available for children. For comparison, normal adult fares in 1937 were 2d per section, up to a maximum of nine sections.

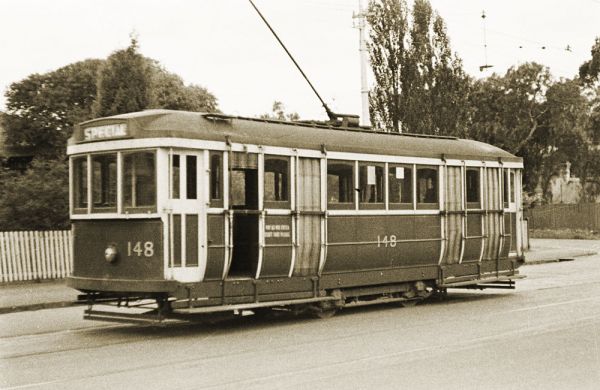

M&MTB all-night tram Q class 148 in an undated pre-World War II view, running a special daytime service. Note the presence of both running boards – the rear running boards on each side were removed in later years, as in the photograph of Q 198 below.- Photograph courtesy F.G. Naylor.

Additionally, regular night services were extended to around midnight, to bridge the gap between the last car (which was typically about 10:30pm) and the new all-night services, which began around 1am. Drivers were paid at a special increased rate, to cover the increased responsibility of collecting fares as well as driving.

All-night services were added on two more routes from 14 March 1937, as further tramcars were available after receiving modifications at Preston Workshops. The routes were:

- Mont Albert to City

- East Kew to City

To reduce the operational cost of all-night services, later that year Chairman H.H. Bell negotiated with the State Electricity Commission and the Melbourne City Council Electric Supply Department to provide power to the M&MTB for a concessional tariff, saving £2550 per annum – about 1.4% of the total power bill, or the approximate all-night operational loss. In the 1937 annual report, Bell advised that the all-night trams were running at a small loss, but this was more than offset by the revenues from the new Sunday morning services, which had been introduced the same financial year. He also expected that patronage would improve over the following summer months.

However, the Australian Tramway & Motor Omnibus Employees Association (ATMOEA) – the union representing drivers and conductors – opposed the use of one-man trams and buses in May 1937, on the grounds that they involved a danger to the public, and imposed too great a strain on the driver-conductors manning these vehicles.

Bell responded that the one-man all-night and Footscray services were projected to lose £3,000 and £20,000 respectively per annum, and the Holden Street and Point Ormond one-man services were similarly unprofitable. Running two-man crews on these services was just uneconomic, and would result in those routes being abandoned. He also stated that conditions of employment for M&MTB crews compared favourably with private bus lines using one-man crews – 48 hours per week versus 60 hours – and that M&MTB pay rates for driver-conductors were significantly higher than its private counterparts. This was backed up by the large numbers of M&MTB drivers applying for transfers to the one-man services.

Most compellingly, Bell advised that the statistics demonstrated there was no difference in the accident rate between one-man and two-man crewed vehicles. Despite the strength of his arguments, this was an industrial issue that would not go away.

Melbourne’s cool winter nights had direct impact on passenger comfort, as the all-night trams were unheated. In 1939 the Chairman, H.H. Bell, promised to undertake an investigation into providing heating for the all-night cars. However, it appears that the onset of the Second World War prevented this worthwhile improvement from proceeding further. It was not until the introduction of the Z class trams in 1975 that heated tramcars became common for the Melbourne travelling public.

The financial year 1940-41 saw the all-night trams run at a profit for the first time, carrying 506,931 passengers for a revenue of £12,235, resulting in an operating surplus of £386, compared with a deficit of £2,064 for the previous year. The increased patronage was attributed to wartime conditions, including the implementation of petrol rationing and the introduction of early and late shifts at munitions works.

Operation of all-night trams was not without some risk for their drivers. Normally, this was restricted to managing inebriated late-night passengers, but occasionally more serious events were encountered. On 27 April 1940, a driver of an all-night tram, William G. Rickard, was held up at pistol point by two young men in Whitehorse Road, Balwyn. The two men hailed the tram at the Narrak Road stop, demanding he hand over his conductor’s bag. Driver Rickard foiled the robbery attempt, by smartly driving off, causing the offenders to jump off the tram.

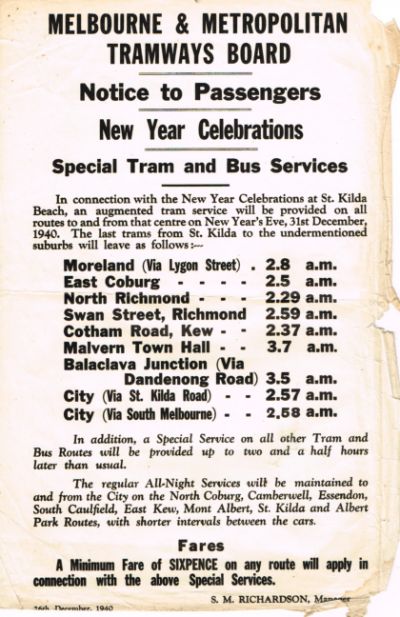

M&MTB special passenger notice advising of the special night services

for the 1941 New Year celebrations at St Kilda Beach.

M&MTB special passenger notice advising of the special night services

for the 1941 New Year celebrations at St Kilda Beach.- From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection.

Mrs Hazel Scott, a war-time conductress working out of Hawthorn Depot, recounted in later years an incident from 1943 regarding an all-night service. One morning she was rostered on the first car, so she was waiting at the Burwood terminus for the last all-night car to take her to work. As the tram approached she saw the driver was a man she knew well, so she waved at him. The driver – named Ted in her recollection – took his right hand off the brake valve handle and waved back. However, Ted had neglected to apply the brakes, so the tram shot off the end of track and ended up sitting in the bitumen all the way across Warrigal Road.

Needless to say, Hazel did not make it to work in time to clock on. The incident was officially ascribed to a sticky brake valve, combined with the rising sun dazzling the driver.

In July 1941, the Commonwealth’s Liquid Fuel Control Board – responsible for managing Australia’s wartime fuel stocks, together with the operation of the petrol rationing scheme – contacted the M&MTB to investigate means of reducing petrol consumption, as Australia’s fuel position had become dire.

The M&MTB resolved to introduce all-night tram services on all lines, to replace private bus services. Three private bus lines – Essendon-Brighton, Melbourne Public Library-Carnegie, and Camberwell Junction-Port Melbourne – were wound up, and their buses purchased by the M&MTB at a mutually agreed price. Buses of other private operators were leased for the duration of the war, or until petrol again became freely available. All the newly acquired buses were to be used to augment transport services to munition works and other metropolitan defence factories. The Liquid Fuel Control Board approved the plan.

From 27 July 1941, all-night trams were operated on 20 routes:

- City to Burwood

- City to Camberwell

- City to Carnegie

- City to Coburg

- City to East Brighton

- City to East Coburg

- City to East Kew

- City to East Malvern

- City to East Preston

- City to Elsternwick

- City to Essendon

- City to Glen Iris

- City to Mont Albert

- City to North Coburg

- City to South Melbourne Beach

- City to South Melbourne and St Kilda Beach

- City to St Kilda Beach

- City to Wattle Park

- City to West Coburg

- City to West Maribyrnong

Fares were set at 4d for one or two sections, and 8d for three or more sections. However, fares from St Kilda to the City were set at a concessional rate of 6d. Regular adult ticket prices were unchanged from 1937.

All-night tram services were to be hourly, but scheduled such that inner sections of routes shared between two or more lines would have trams at 30 minute intervals, such as on the Burwood and Wattle Park routes that shared tracks from Princes Bridge to Camberwell Junction.

This scheduling policy came in useful for the author’s father, Private N.F. Jones, in 1944. He had gone absent without leave from his unit in Brisbane to see the Melbourne girl who would later become his wife. She lived with her parents in Warrigal Road, Burwood. He left her residence to catch an all-night Burwood tram, but arrived to see it disappearing down Toorak Road. If he waited an hour for the next tram, Private Jones would miss the northbound troop train he had planned on using to return to Brisbane, and miss his unit’s next pay parade – which would result in him being placed on a charge. He ran one mile along the steep hills of Warrigal Road, his duffle-bag on his shoulder, to Riversdale Road, in time to catch the next city-bound tram from Wattle Park. He made the troop train waiting at Spencer Street station without incident, avoiding a patrol of military police on the way, and managed to return to Brisbane without detection.

The removal of the private bus services on 6 August 1941 was not universally popular, as areas in Brighton and East Caulfield were left without an all-night service. The affected public felt unavailability of petrol due to war conditions was an insufficient reason for the inconvenience they suffered.

Additional all-night tram services were progressively added, as more one-man tramcars became available:

- West Preston to Thornbury shuttle (2 August 1941)

- City to Toorak (10 August 1941)

- North Richmond to St Kilda Beach (23 August 1941)

Blackout regulations [3] were introduced on all forms of transport in February 1942 due to hostilities commencing with Japan. These led to a reduction in the speed of night-time tram services for safety reasons. This change affected schedules, and would remain in place until August 1945.

The M&MTB came under criticism for the condition of the all-night tramcar fleet in July 1949. At that stage, almost all of the tramcars dedicated to all-night service were over twenty years old, and were showing their age. Some of the S class cars were over thirty years old. It was claimed that the all-nighters were “a relic of the dark ages, and a disgrace to any modern transport system”.

Bell responded by stating the M&MTB was the only transport authority in Australia that still operated an all-night service, as all others had ceased at the end of the war or shortly afterwards. Only 25% of the operating cost was being recovered, but the M&MTB was happy to provide the service, as it valued the appreciation of its patrons who used the all-night trams.

In December 1947, the M&MTB was threatened with industrial action by the AMTOEA over one-man trams and buses, including all-night trams. The union threatened to ‘black-ban’ all-night services unless two-man crews were instituted, or pay rates increased. The M&MTB stated that all-night driver-conductors were already paid double time, and worked fewer hours than other traffic staff.

A general strike followed from 3 January to 17 January 1948 over a number of issues including one-man crews. However, later arbitration did not resolve the one-man issue, although many of the other areas of dispute were settled.

A 1953 view of all-night tram Q class 198 working its daytime duty on the Elsternwick-Point Ormond shuttle service in Glenhuntly Road, just before crossing over the VR St Kilda-Brighton Beach line, heading for the beach terminus.- Photograph courtesy Noel Reed.

Another strike led by the ATMOEA occurred from 23 February to 23 April 1950, resulting in the cancellation of all tram and bus services. After collapse of the two-month strike and return to work the following day, normal daytime services resumed, but none of the all-night services returned due to lack of manpower. Many of the striking traffic staff had started work with other employers and did not return to employment with the M&MTB. Limited all-night services on a small number of routes resumed on 2 May 1950, with 60-minute service intervals replaced by 75-minute intervals. The routes were:

- Essendon to Glen Iris

- Carnegie to North Coburg

- Burwood to Princes Bridge

- Mont Albert to South Melbourne Beach

The East Preston all-night tram service was replaced by extension of the Garden City to Northcote all-night bus service. Two months later, the ATMOEA pressed the M&MTB for full restoration of the all-night service for the convenience of the travelling public and tramway employees travelling to and from early and late shifts. The new Chairman, R.J.H. Risson, promised to take the matter under consideration, but failed to give any commitment to full resumption of service, despite ongoing pressure from the media to do so.

On 22 July 1950, all-night services returned to operating at 60 minute intervals, and service was resumed on the following lines:

- City to Camberwell

- City to East Brighton

- City to East Coburg

- City to East Kew

- City to St Kilda Beach

- Prince Bridge to Wattle Park

- City to West Preston

All-night fares were increased from 24 December 1950. One or two sections were now 6d, three sections 9d, four sections 1/-, five sections 1/3, and six sections or more were set to 1/6. There was criticism in the media over the increase, stating that for some passengers it was an effective increase of over 100%. In response, the Board advised that the availability of workers’ concessional fares for all-night services was unlikely, as most workers who frequented the service received high penalty rates for shift work. Furthermore, all-night services were run at a loss to the M&MTB, so it was necessary to minimise the loss as far as possible. Adult daytime fares were also increased with effect on the same day, becoming 3d for a single section, 5d for two sections, and each additional section costing an extra 1d to a maximum fare of 8d.

Further all-night services would resume over the next two years:

- City to East Malvern (3 September 1951)

- City to West Maribyrnong (7 October 1951)

- North Richmond to St Kilda Beach (19 November 1951)

- City to Toorak (24 February 1952)

Additionally, on 14 October 1951 the Essendon all-night service was extended from Birdwood Street to Matthews Avenue, with some trips going to Essendon Aerodrome. In March 1952, the East Kew service was extended to Mont Albert.

In May 1952, the ATMOEA again threatened industrial action over one-man crewing of trams and buses, although no immediate strike action eventuated. The Victorian state secretary of the ATMOEA, Clarrie O’Shea, took the issue of one-man crews to an ATMOEA Federal Council meeting, seeking mandatory provision of two-man crews across Australia, but was unable to obtain a majority to support his position.

Despite his loss at the Federal level, O’Shea continued the dispute, which in November 1953 crystallised around the rostering of 41-seat buses on the Clifton Hill to Point Ormond route with one man crews, in place of the 32-seat buses previously operated. This issue would see frequent industrial action over the next four years, which was basically settled by the M&MTB not rostering 41-seat buses with one-man crews, despite Arbitration Court findings supporting its position. Future bus acquisitions by the M&MTB would be limited to 32 seats.

This ongoing dispute, however, had no direct bearing on the provision of one-man all-night tram crews.

All-night tram services were replaced by less frequent bus services – 75 minutes as opposed to 60 minute intervals on the trams – as from the evening of 16/17 February 1957, bringing the services to an end after 20 years. The rationale behind the change was to decrease costs through reduction of service and changes in routes, as all-night tram revenues had been falling for some years. It also enabled retirement of obsolete single truck tramcars [4], reducing the maintenance budget, through replacement with more modern buses.

The decline in all-night tram patronage was primarily driven by the increased usage of private motor cars, which affected post-war public transport generally. However the introduction of television services in 1956 would have been a significant contributing factor for the cancellation of all-night tram services, as this resulted in a significant change in leisure patterns affecting attendances at dances, cinemas, theatres and other social venues.

Withdrawn all-night cars on rotten road – the siding for trams due to be scrapped – at Preston Workshops in May 1957, after the end of all-night services three months previously. From left to right the trams are Q 200, X 218, X 217, two unidentified Q or R class trams and T 178. X 217 is now in the collection of the Melbourne Tram Museum.- Photograph courtesy Ian Brady.

Forty years later, the State Government decided to run a trial of all-night trams on a single route, to run early Saturday and Sunday mornings. The service was known and marketed as Route 99 Nightlink, and ran a 20-minute service over the route from Melbourne University to North Fitzroy via Swanston Street, Batman Avenue [5], Swan Street, Church Street, Chapel Street, Carlisle Street, Esplanade, St Kilda light rail, Spencer Street, Collins Street and Brunswick Street.

The route was designed to take in areas known for their vibrant nightlife, to provide a service directed towards to the target market of young nightclubbers. A class tramcars and crews from Kew Depot were used, and normal Met fares applied. Nightlink initially ran for a five-week period from 28 February 1997, but was adversely affected by industrial action. As insufficient data was collected to judge the viability of the experiment, the trial was repeated for a longer period, from 1 November 1997 to 28 March 1998.

The Nightlink service was not renewed beyond the second trial.

As from 1 January 2016, Yarra Trams introduced weekend all-night tram services on selected routes, under the Andrews State Government Night Network program. The major objective of the program was to provide safe, reliable public transport that catered to patrons of Melbourne’s nightlife. The routes operated were:

- Route 19 – North Coburg to Flinders St Station

- Route 67 – Melbourne University to Carnegie

- Route 75 – Vermont South to Etihad Stadium Docklands

- Route 86 – Bundoora RMIT to Waterfront City Docklands

- Route 96 – East Brunswick to St Kilda Beach

- Route 109 – Box Hill to Port Melbourne

Yarra Trams E class 6003 on Night Network all-night service in LaTrobe Street, during White Night 2016 (evening of 20 February 2016).- Photograph courtesy Mal Rowe.

In April 2017, the State Government announced that the Night Network weekend all-night tram services on selected routes would remain, with the 30-minute service interval retained. The cost of operation was, however, higher than expected.

However, unlike the original all-night services, which were strongly oriented to meeting the demands of manufacturing industry workers, current all-night services are almost entirely intended to serve recreational passengers.

Bibliography

The Age (1901), Sydney Trams – All Night Service to be Tried, 2 September 1901

The Age (1908), The Sydney Tramways – What Electrification Has Done, 21 November 1908

The Age (1911), All-Night Tram Service – Successful Sydney Venture, 25 April 1911

The Age (1920), All-Night Trams – Tramway Board’s Proposal, 5 November 1920

The Age (1921), All-Night Trams – Probable Introduction Shortly, 15 February 1921

The Age (1921), All-Night Trams – Experiment on Hawthorn Line, 9 March 1921

The Age (1921), General News – All-Night Trams, 1 April 1921

The Age (1921), All-Night Trams – Hawthorn Service to be Discontinued, 19 August 1921

The Age (1921), All-Night Trams – Service Now Discontinued, 30 September 1921

The Age (1925), All-Night Trams – Inauguration Considered, 28 July 1925

The Age (1926), All Night Transport – Trams or Buses Suggested, 4 May 1926

The Age (1929), General News – All-Night Trams Unlikely, 19 July 1929

The Age (1934), Wake Up, Melbourne – All-Night Trams, 30 August 1934

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams – Board’s Experiment, 4 September 1936

The Age (1936), Bus Proprietors’ Protest, 7 September 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams – Opposition by Motor Interests, 7 September 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams – Board Determined, 9 September 1936

The Age (1936), All Night Trams, 15 September 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams – Opposition by Bus Owners, 1 October 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams, 2 October 1936

The Age (1936), Cr. A.G. Wales MLC, Re-elected Lord Mayor, 10 October 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams to operate in December, 15 October 1936

The Age (1936), All-Night Trams – Support for Bus Operators, 28 October 1936

The Age (1937), Sunday Night Trams – Details of Extended Services, 10 February 1937

The Age (1937), All-Night Trams – Reduction in Losses, 21 October 1937

The Age (1941), All-Night Tram Extensions, 11 July 1941

The Age (1941), All-Night Trams – Many Workers Will Be Affected, 26 July 1941

The Age (1947), Tram Men’s Threat – All-Night Crew, 11 December 1947

The Age (1949), Mr. Bell Defends ‘All-nighters’, 30 July 1949

The Age (1950), All-night Trams Running Again, 2 May 1950

The Age (1950), More All-night Trams Sought, 5 July 1950

The Age (1950), Christmas Eve Rise for Tram Fares, 20 December 1950

The Age (1950), ‘All-Nighter’ Fares to Stay, 29 December 1950

The Age (1951), All-Night Trams for East Malvern, 1 September 1951

The Age (1952), All-night Tram on Toorak Line, 14 February 1952

The Age (1952), All-Night Trams to be Extended, 23 February 1952

The Age (2015), All-night weekend public transport kicks off at New Year’s with new name, 30 October 2015

The Age (2016), 10,000 use night trains, trams and buses on first weekend of 24 hour services, 8 January 2016

The Age (2016), Late-night revellers turning to trains, trams and buses over taxis, 19 June 2016

The Age (2016), Ghost buses haunt the roads but Night Network trial extended for six months, 2 August 2016

The Age (2016), The high cost of Melbourne’s all night weekend public transport trial, 13 October 2016

The Age (2016), Fewer than 15,000 used Labor’s Night Network on April weekend: Opposition, 23 October 2016

The Age (2017), All night public transport to keep Melbourne on the move, 22 April 2017

The Argus (1911), All Night Trams – Public Demand – Petrol Engines Suggested, 17 January 1911

The Argus (1911), All Night Trams – The Company’s View – Cost Hardly Warranted, 19 January 1911

The Argus (1911), All Night Trams – The Cheapest Method of All – The Horse Cars, 20 January 1911

The Argus (1911), All-Night Trams, 27 January 1911

The Argus (1911), All-Night Trams, 30 January 1911

The Argus (1921), Train and Tram Fares, 5 March 1921

The Argus (1921), Hawthorn All-Night Trams – Unprofitable Service to Cease, 19 August 1921

The Argus (1921), Hawthorn All-Night Trams, 26 September 1921

The Argus (1921), Hawthorn All-Night Trams – Railway Workers Persistent, 1 October 1921

The Argus (1925), All-Night Trams – New Proposal Made, 28 July 1925

The Argus (1935), Tram Fares Not 100 Percent Higher, 17 April 1935

The Argus (1936), All-Night Trams – Board Makes Decision, 4 September 1936

The Argus (1936), All-Night and Sunday Morning Trams – Baptists Anxious – Temptation to Young, 14 October 1936

The Argus (1937), All-Night Trams – Service May Begin on February 14, 22 January 1937

The Argus (1937), 403 Use Night Trams – Board Is Well Satisfied, 16 February 1937

The Argus (1937), All-Night Trams – First Week: 4,644 Patrons, 23 February 1937

The Argus (1937), All-Night Trams Show Loss – £3000 per Year – Union ‘One Man’ Protest, 7 May 1937

The Argus (1937), Small Loss on Night Trams – Service to Go On, 19 August 1937

The Argus (1937), More All-Night Trams? – Summer Possibility, 21 October 1937

The Argus (1939), Heaters in All-Night Trams, 27 June 1939

The Argus (1940), Hold-up Foiled, 29 April 1940

The Argus (1941), More All-Night Trams Plan, 9 July 1941

The Argus (1941), All-Night Buses Cancelled, 18 July 1941

The Argus (1941), All-Night Trams on 20 Routes, 25 July 1941

The Argus (1941), All-Night Tram Extension, 2 August 1941

The Argus (1941), No All-Night Tram Extensions, 7 August 1941

The Argus (1941), New All-Night Tram Service, 23 August 1941

The Argus (1942), Lower Night Speeds for Trams, 12 February 1942

The Argus (1950), Get Home Now – Eight New Lines, 22 July 1950

The Argus (1950), Increased All-Night Tram Fares Soon, 2 December 1950

The Argus (1951), Night Trams for Malvern, 3 September 1951

The Argus (1952), All night trams in danger, 31 May 1952

The Argus (1956), Buses will take over from all-night trams, 25 October 1956

Butlin, S.J.C.L. (1955), Australia in the War of 1939-1945 – Volume III – War Economy 1939-1942, Chapter 13 page 450, Australian War Memorial

Keenan, D.R. (1979), Tramways of Sydney, Transit Press

M&MTB (1937), Cable and Electric Tramways and Motor Omnibuses – Sections and Fares

M&MTB (1937-1957), Annual Reports

Shepparton Advertiser (1936), All-Night Trams for City – Board Firm Though Church Protests, 15 October 1936

Storey, D. (2016), Melbourne Electric Tramways Gunzel Notes

Waldron, H. (2009), History of Melbourne Tram Routes from 1950 to 2009, Yarra Trams

Yarra Trams (2017), Melbourne Tram Network

Other sources

Personal recollection – Mrs Hazel F. Scott

Personal recollection – Mr Noel F. Jones

All-night cars T class 178 and Q class 142 amongst a gaggle of W2 class and Q class trams on the outside roads at Essendon Depot in the late 1930s.- Photograph by the Nowell brothers.

Footnotes

[1] Prior to 4 October 1936, Melbourne trams did not operate on Sunday mornings, in order to preserve the sanctity of Christian church services.

[2] The Minister for Public Works was the State Cabinet minister responsible for overseeing the M&MTB.

[3] Blackout regulations minimising outside lighting during the Second World War were intended to prevent crew of enemy aircraft from identifying their targets by sight. Additionally, in coastal areas blackout regulations helped protect shipping from being seen in silhouette against city lights from enemy submarines further out to sea.

[4] Many of the one-man cars were over thirty-five years’ old at the cessation of the M&MTB all-night tram service.

[5] The Nightlink Route 99 trams were the only scheduled passenger services that used the double track curves put in from Swanston Street to the Batman Avenue terminus. These curves were removed with the abandonment of Batman Avenue for the Federation Square project, which resulted in route 70 being diverted from Swan Street, behind the Tennis Centre and across the Exhibition Street bridge over the rail yards into Flinders Street.

A2 class tram 286 in Chapel Street, Prahran on a Nightlink route 99

service in 1997.

A2 class tram 286 in Chapel Street, Prahran on a Nightlink route 99

service in 1997.- Photograph courtesy Jeff Bounds.